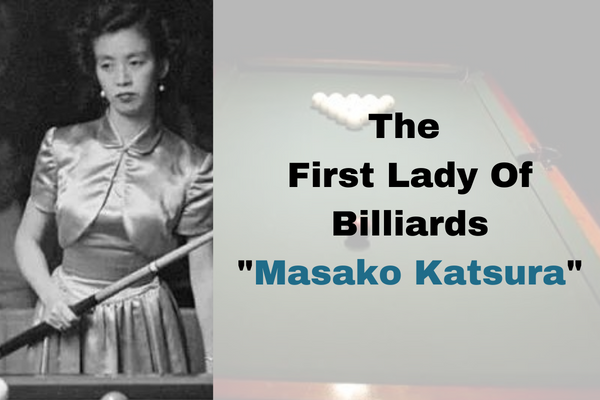

The Japanese woman Masako Katsura was known for her credibility and is considered the first lady of billiards.

In the 1950s, she played an active role in male-dominated professions worldwide. However, Katsura earned a high reputation in her field.

Become familiar with her life to discover when she moved to the United States and when she died, as well as how she started her career and why she did not marry.

Masako Katsura’s Early Life and Career

As a result of her father’s tragic death, Masako was raised in her hometown of Tokyo, Japan, by her mother since she was born there in 1913.

At a young age, she had a keen interest in sports and began playing billiards as a career.

Billiards has been her mother’s suggestion to continue her profession through thick and thin. She has been supported under every circumstance by her mother.

As a result, my mother advised me to play billiards to increase my fitness and strength. Since I was always weak and tired, she recommended that I play billiards to increase my fitness and strength.

Katsura’s brother-in-law owned one of the famous billiard halls in Tokyo in 1920.

In the course of discovering her talents, Katsura became passionate about the game of billiards.

She started playing billiards every day to follow her mother’s dream.

To achieve high goals, she worked hard and practiced for a long time to build better credibility.

As a result, she developed a knack for trick shots when she practiced consistently at a very young age.

The Japanese women’s straight-rail championship was won by Masako Katsura when she was only 15 years old.

After gaining the attention of Japan’s former champion, Kinrey Matsuyama, Katsura was taken under his care and taught three-cushion billiards under his guidance.

Masako Katsura moved to America to pursue her career

A different environment than Tokyo welcomed Masako Katsura when he migrated to California in 1951.

Her favorite billiard hall in Tokyo consisted of a hundred women’s halls. Her extraordinary skills had to compete against males in a billiard hall in California where most players were male. Katsura commented, “So far, I have observed only one woman playing billiards.

There is a perception that billiard parlors are men’s places. I would like to see a women’s only billiard parlor.” In her aspiring billiard career, she was hampered by the European Wars and provided military service to represent her country in the war. Katsura performed a one-woman show for Japanese soldiers during the war; afterward, she relocated to perform billiard tricks for American soldiers. She gained international recognition for her war performance, and her career has developed internationally.

According to one American soldier, Masako Katsura is better than her father, Welker Cochran, a world-class billiards champion. Katsura was encouraged to visit the United States by Cochran. Before her performance, he invited her to come to the U.S.

To compete in the men’s national championship, she had to win the national women’s billiards tournament.

Success In The International Billiard Halls

Her career zoomed in as a billiard player during the 1950s.

Because of Katsura’s credibility, Welker Cochran became Katsura’s manager and told the newspapers that.

I am convinced that it is now possible for the game to finally have a woman playing with the skill necessary to compete against the greatest of men players.

There was extensive coverage of Katsura in the national press, with the media placing more emphasis on her gender than on her capabilities.

Newspapers characterized the champion as “a real Japanese cue-tee.”

She looks like the wisp of a woman who cannot blow a feather away but can blow billiard balls away or behave like a chastened child.”.

Billiard players respected her, and Willie Hoppe said that.

The girl is marvelous. She’s going to win her share of matches against the best of them.”

A Woman Who Changed The Concept Of Gender Difference

As a star of network television shows and an international champion at international tournaments, Masako Katsura became famous in 1958. As a result of a tough loss in 1961, Katsura retired.

In 1976, Masako Katsura went on a 100-point run at a San Francisco billiards parlor after picking up a cue and a ball.

A group of professional billiard players formed the Women’s Professional Billiard Association after seeing a successful female competitor in the 1970s.

Death of Masako Katsura In 1995.

As soon as she retired, Katsura moved back to Japan to live with her sister, Noriko, until her death. It was 1995 when Katsura died after living with her sister for five years.

There was, however, one event held in Japan broadcast on SKY PerfecTV called Katsura Memorial: The First Ladies Three Cushion Grand Prix. As a memorial to Katsura, a tournament was held in 2002.

Billiards’ first lady has earned an enormous reputation in her career and is now regarded as a legend.

A Tribute to Masako Katsura by Google Doodle

On Google’s home page, a Google Doodle was created to honor her on International Women’s Day in 2021. She was described in the Doodle as a woman with an influential career and exceptional accomplishments throughout her career

World Three Cushion Billiard Tournament championship 1952

As a result of her success at the 1953 World Three-Cushion Billiards Tournament, she became an international sensation.

She is the only girl to have competed in the billiards tournament in the 1942 New York State Championships after Ruth McGuinness.

The previous champion, Willy Hoppe, was 64 years old at the time, and he also competed in the following competition. According to pre-event speculation, Katsura would not receive 10 points if Hoppe and Katsura played each other.

In addition to Katsura, Matsuyama, Willy Hoppe, Joe Camacho (from Mexico), Herb Hardt (from Chicago), Arthur Rubin (from New York), Arthur Rubin (from New York), and Arthur Rubin (from Los Angeles), many individuals also attended the tournament, including Katsura, her trainer and friend Matsuyama, Willy Hoppe, Joe Proquita, Ray Kilgore, Jay Boseman, and Irving Crane.

There were 45 games that would be played in a round-robin format at Cochrane’s “924 Club” during a 17-day tournament ending on March 22, 1952.

Reports indicate that this was the largest tournament since before World War II.

In light of this, it is not surprising that the first prize was $ 2,000 as well as a large exhibition fee, and the following awards were $ 1,000, $ 700, $ 500, $ 350, $ 300, $ 250, and $ 250, up to the eighth position.

Willie Hoppe won this championship and resigned after successfully defending it in 1952.